Physiological Differences Between Men And Women Aren't As Striking As Many Believe

For decades, popular writers have entertained readers with the premise that men and women are so psychologically dissimilar they could hail from entirely different planets. But a new study shows that it's time for the Mars/Venus theories about the sexes to come back to Earth.

From empathy and sexuality to science inclination and extroversion, statistical analysis of 122 different characteristics involving 13,301 individuals shows that men and women, by and large, do not fall into different groups. In other words, no matter how strange and inscrutable your partner may seem, their gender is probably only a small part of the problem.

"People think about the sexes as distinct categories," says Harry Reis, professor of psychology at the University of Rochester and a co-author on the study to be published in the February issue of the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. "'Boy or girl?' is the first question parents are asked about their newborn, and sex persists through life as the most pervasive characteristic used to distinguish categories among humans."

But the handy dichotomy often falls apart under statistical scrutiny, says lead author Bobbi Carothers, who completed the study as part of her doctoral dissertation at Rochester and is now a senior data analyst for the Center for Public Health System Science at Washington University in St. Louis. For example, it is not at all unusual for men to be empathic and women to be good at math – characteristics that some research has associated with the other sex, says Carothers. "Sex is not nearly as confining a category as stereotypes and even some academic studies would have us believe," she adds.

The authors reached that conclusion by reanalyzing data from 13 studies that had shown significant, and often large, sex differences. Reis and Carothers also collected their own data on a range of psychological indicators. They revisited surveys on relationship

interdependence, intimacy, and sexuality. They reopened studies of the "big five" personality traits: extroversion, openness, agreeableness, emotional stability, and conscientiousness. They even crunched the numbers on such highly charged and seemingly defining gender characteristics as femininity and masculinity. Using three separate statistical procedures, the authors searched for evidence of attributes that could reliably categorize a person as male or female.

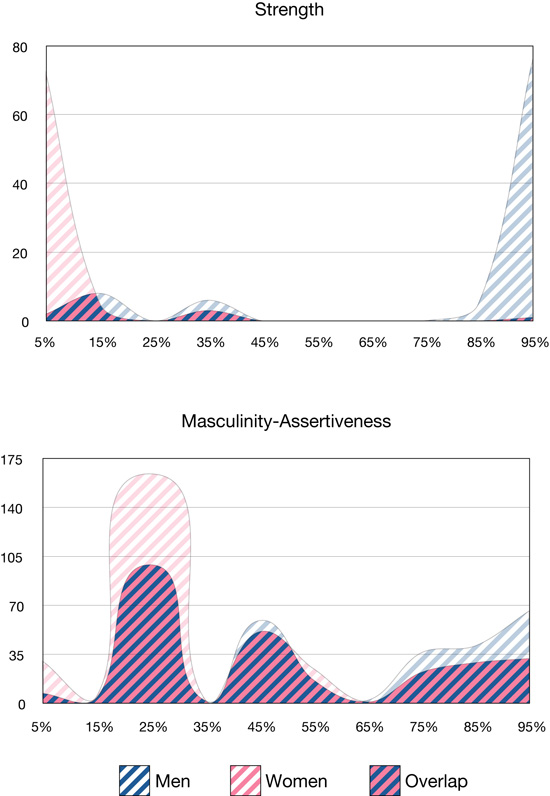

The pickings, it turned out, were slim. Statistically, men and women definitely fall into distinct groups, or taxons, based on anthropometric measurements such as height, shoulder breadth, arm circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio. And gender can be a reliable predictor for interest in very stereotypic activities, such as scrapbooking and cosmetics (women) and boxing and watching pornography (men).

But for the vast majority of psychological traits, including the fear of success, mate selection criteria, and empathy, men and women are definitely from the same planet. Instead of scores clustering at either end of the spectrum—the way they do with, say, height or physical strength—psychological indicators fall along a linear gradation for both genders. With very few exceptions, variability within each sex and overlap between the sexes is so extensive that the authors conclude it would be inaccurate to use personality types, attitudes, and psychological indicators as a vehicle for sorting men and women.

"Thus, contrary to the assertions of pop psychology titles like 'Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus', it is untrue that men and women think about their relationships in qualitatively different ways," the authors write. "Even leading researchers in gender and stereotyping can fall into the same trap."

That men and women approach their social world similarly does not imply that there are no differences in average scores between the sexes. Average differences do exist, write the authors. "The traditional and easiest way to think of gender differences is in terms of a mean difference," Carothers and Reis write. But such differences "are not consistent or big enough to accurately diagnose group membership" and should not be misconstrued as evidence for consistent and inflexible gender categories, they conclude.

"Those who score in a stereotypic way on one measure do not necessarily do so on another," the authors note. A man who ranks high on aggression, may also rank low on math, for example. Caution the authors: "the possession of traits associated with gender is not as simple as 'this or that'."

Although emphasizing inherent differences between the sexes certainly strikes a chord with many couples, such simplistic frameworks can be harmful in the context of relationships, says Reis, a leader in the field of relationship science. "When something goes wrong between partners, people often blame the other partner's gender immediately. Having gender stereotypes hinders people from looking at their partner as an individual. They may also discourage people from pursuing certain kinds of goals. When psychological and intellectual tendencies are seen as defining characteristics, they are more likely to be assumed to be innate and immutable. Why bother to try to change?"

The best evidence we have that the so-called Mars/Venus gender division is not the true source of friction within relationships, says Reis, is that "gay and lesbian couples have much the same problems relating to each other that heterosexual couples do. Clearly, it's not so much sex, but human character that causes difficulties."

The findings support the "gender similarities hypothesis" put forth by University of Wisconsin psychologist Janet Hyde. Using different methods, Hyde has challenged "overinflated claims of gender differences" with meta-analyses of psychology studies, demonstrating that males and females are similar on most, though not all, psychological variables.

Those results were not a surprise for Carothers. Raised by two physical education teachers, the self-described tomboy grew up with "all kinds of sporting equipment… I did not question stereotypical attitudes, I just knew that they did not necessarily fit me and the folks I hung out with." That experience, she says, fueled a lifelong interest into the biological basis of behavior. When she discovered in graduate school that she could apply her prowess in statistics to exploring sex differences, the project became "a marriage of two interests."

The authors acknowledge that the study is based largely on questionnaires and may not fully capture real life actions. "Methods that more pointedly measure interpersonal behaviors (how many birthday cards have they sent this year, how many times a month do they call a friend just to see how he or she is, etc.) may more readily reveal a gender taxon," they write.

By the same token, however, as gender roles are liberalized, the authors speculate that new studies may show even less divergence between men and women in the United States. The opposite may be the case in cultures that are far more prescriptive of male and female roles, such as Saudi Arabia, Reis and Carothers predict.

Source: The University of Rochester